The Greenwood Run

I’ve been in combat, shot at, lost my hearing for three weeks from an IED—but all that was tame compared to Laura Marley’s driving.

The first time I rode with her to Greenwood nearly finished me. I didn’t know then that I’d ever do it again—let alone want to.

“Anyone can stop for lights,” she laughed, lighting one Camel Straight off another as her Grabber Blue Mustang roared through Broadway and 28th. Cars braked and swerved, horns blaring. She flicked the butt out the window and laughed again while I tried to drive both feet through the floorboards. The Runaways were screaming Cherry Bomb, drowning out every curse in the city.

“We never stop for anything,” she shouted, eyes locked ahead. “Against the rules.”

“Whose rules?” I asked.

“Mine,” she said. “And the girls’.”

She only slowed for cats—apparently her only sacred exception—and I wondered what that said about the rest of us. I watched her swerve gently around one, whispering, “Watch it, Kitty,” as if she were blessing it.

I was seventy-one years old, wondering if this was how men my age died—surprised, upside down, thinking they had more time.

By the time we skidded into the Greenwood Tavern parking lot, my heart was drumming like a chopper rotor. Inside, I knocked back three beers before I could breathe right again. Laura and her crew were already there—Dorothy in her ’68 Camaro, Maureen in a Charger that rumbled like thunder, Patricia in a Tesla she drove like she wanted to burn out the batteries.

All of them pushing seventy.

All of them certain they weren’t done yet.

“Started as a joke,” Laura said, smoke curling from her lips. “Maureen said we were getting too careful. Too old. So we made our own rule—no stopping, no looking, no fear.”

Dorothy took a long pull from her beer and set it down hard.

“We had trouble last week,” she said.

Laura didn’t look at her. “No, we didn’t.”

“Kid on a bike,” Maureen said. “Twelve, maybe thirteen. Blew through a stop sign on 12th.”

My stomach tightened.

“Laura clipped his back tire,” Dorothy said. “Kid went down.”

“I didn’t hit him,” Laura said.

“You knocked him over,” Dorothy said.

“He popped right back up,” Laura snapped. “Kids bounce.”

“His arm was bleeding,” Maureen said. “And he was crying.”

“Because his mother was screaming,” Laura said. “He wasn’t broken.”

“The cops came,” Dorothy said.

I stared at Laura. “The cops?”

“They let us go,” Laura said. “No witnesses. No damage. Nothing worth writing down.”

“You didn’t wait,” I said.

She met my eyes then. “I wasn’t stopping. That’s the rule.”

“Even when someone gets hurt?”

“He wasn’t hurt,” she said. “He was scared. There’s a difference.”

I wasn’t sure there was.

I called an Uber home. As I left, Laura cupped her hands around her mouth.

“What the hell, Pussy, you wanna live forever?”

“No,” I said. “Just a little longer.”

***

She called Saturday morning.

“Breakfast at Mabel’s?”

“I’ll drive,” I said.

“Figured you would.”

In my sensible Altima, Sinatra murmured Summer Wind while I kept both hands steady at ten and two. Laura wore jeans, a soft blue sweater, and that grin that always looked half a dare. At sixty-eight, she still moved like the world was supposed to keep up.

Over pancakes, she told me about her daughter in Phoenix, her book club’s latest depressing pick, the good wine. I told her about my doctor’s visit, my son, the grocery store that didn’t carry my brand of coffee anymore.

“The important things,” she said.

After breakfast, we drove. Out past the suburbs, past the last traffic light, where the sky opened wide. She rolled down her window, the October air spilling in. When I took her hand, she laced her fingers through mine.

“This is nice,” she said.

“Yeah.”

“But I’m still going to Greenwood on Thursday.”

“I know.”

“You’re invited.”

“I’ll meet you there.”

She squeezed my hand. “Deal.”

She stopped for every crosswalk on the way back. I wondered if that was for me—or the kid on the bike.

***

That became our rhythm.

Tuesdays and Saturdays were ours—my car, my rules, Sinatra low and steady. Thursdays were hers—her Mustang, her posse, her madness. And me driving separately.

“Worried?” she asked one night.

“I don’t worry.”

“You do. I can tell.”

“Maybe.”

“I’m a good driver.”

“You’re a lunatic.”

“I’m a good lunatic,” she said, grinning. “Sixty-eight years and not a scratch.”

“You’ve used up all your luck.”

“Then I’d better keep going before it runs out.”

I didn’t tell her luck doesn’t work that way.

***

Three months later, she asked me to stay over. Her place was small, cozy, cluttered with books and unwatered plants. She made pasta, I brought wine. We talked through an old movie neither of us cared about.

“I’m glad you’re here,” she said.

“Me too.”

“I mean here. In my life.”

“Better late than never.”

She smiled. “Forty years married to a good man who never once scared me. I think that’s what I miss most—the feeling that something might happen.”

“You’ve got plenty happening now.”

“Yeah,” she said softly. “You.”

She kissed me. Smoke, wine, and something wild.

***

Winter came. I kept meeting her at Greenwood after The Run, arriving safe, sane, and five minutes late.

“You missed a good one,” Dorothy would say.

“Chicken,” Maureen would add.

I’d raise my beer. “Alive.”

Then one Thursday, Patricia wasn’t there.

“She pulled over,” Laura said. “Called Dorothy. Said she was done.”

“Smart woman,” I said.

“Or scared,” Laura said.

Dorothy shifted. “Or tired of almost killing someone.”

Laura’s jaw tightened. “That again?”

“How long before it’s worse?” Dorothy said. “How long before it’s us?”

Later, Laura stared into her martini. “Dorothy’s hip is going. Maureen can’t see at night. One day, it’ll be me who can’t anymore.”

“There’s no shame in stopping,” I said.

“Isn’t there?” she asked. “My whole life I’ve been the one who goes.”

***

Spring came early. We drove south one Saturday, windows down, Sinatra crooning The Way You Look Tonight.

“I need to tell you something,” Laura said.

“Okay.”

“I’m scared.”

“Of what?”

“Of stopping.”

I pulled onto the shoulder. Empty road. Open sky.

I looked at her—really looked at her—and saw the tremor in her fingers that had nothing to do with age and everything to do with the silence of the road. For years, I’d used my hearing loss and my combat pay as an excuse to hide in the quiet, wrapped in the safety of seatbelts and speed limits. But looking at Laura, I realized I’d been mistaking “waiting” for “living.” She wasn’t just driving fast to be reckless; she was driving to stay ahead of the ghost of the woman she was supposed to become—the one who sat still and faded away. I didn’t want to watch her fade from the rearview mirror of my Altima. I wanted to be in the seat next to her when the engine roared.

“Next Thursday,” I said, “I’m riding with you.”

She turned. “You don’t have to.”

“I know.” I swallowed. “And if something happens—if someone gets hurt—I’ll own that too.”

She stared at me, then laughed. “You’re insane.”

“Probably.”

“You’ll have a heart attack.”

“Maybe. But I’ll have it with you.”

She kissed me. “Thursday. Four-thirty.”

***

Thursday came too soon.

The Mustang rumbled in my driveway like a dragon. The Runaways were screaming I Love Playing with Fire.

“Last chance,” she said.

“Drive.”

She did.

We shot through Broadway and 12th. Horns erupted. Tires screamed. I watched her hands—steady, fierce—threading chaos with someone who still believed she could outrun time.

A cat darted out. She missed it by inches.

“Watch it, Kitty,” she whispered.

Then we were there. Gravel. Silence. The engine ticking like it had something to say.

“Well?” she asked.

My heart hammered. My hands shook.

“Again,” I said.

She laughed and kissed me like we were twenty.

***

Later, she drove me home slowly, carefully, Sinatra low, as if the night itself were watching to see which version of her would win.

Inside, I poured a bourbon and called my son.

“Dad?”

“Just wanted to tell you I’m in love.”

“At seventy-one?”

“At seventy-one.”

He laughed. “Good for you, Dad.”

“Yeah,” I said, smiling. “Good for me.”

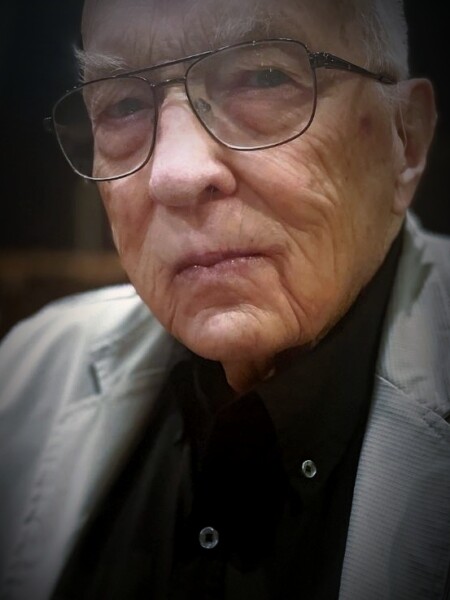

Dale Scherfling is newspaper veteran of 30 years, serving as a sportswriter, columnist, editor and photographer and a retired Navy journalist and photographer. His work has been accepted by Letters Journal, The Blotter Magazine, Third Act Magazine, Yellow Mama, Close to the Bone, Flash Phantom, Does it Have Pockets Magazine, Lost Blonde Literary, All Hands Magazine, Pacific Crossroads, Daily Californian, Naval Aviation Magazine, Propeller Magazine, and Buckeye Guard Magazine. He is the recipient of three U.S. Army Front Page Journalism Awards. He is also a college lecturer and photojournalism, photography and music instructor.